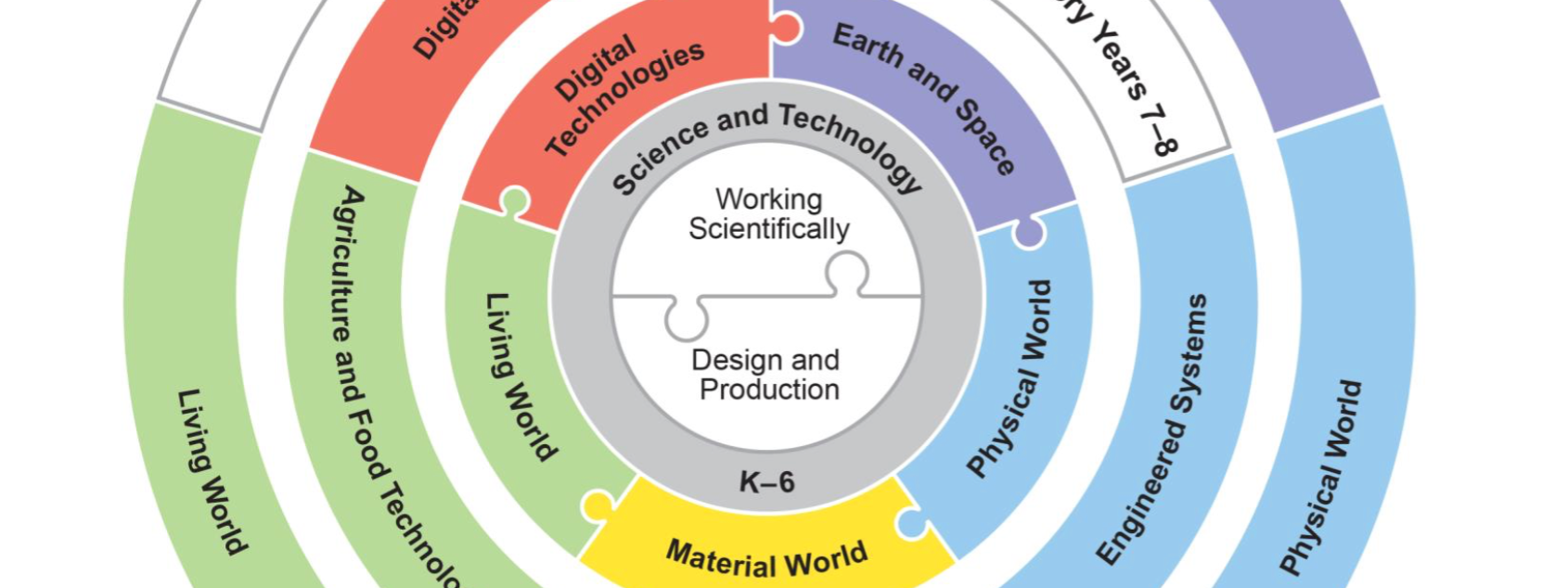

In the final weeks of 2017 a new Science & Technology Curriculum for Kindergarten to Year Six slipped into the schools of New South Wales. What does this new curriculum bring and what does it reveal about the nature of learning as we approach the year 2020?

The Science and Technology Curriculum was updated quite recently. In 2012, it was released as part of the curriculum updates linked to the adoption by states of the Australian Curriculum developed by ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). For some time now teachers have been expecting an update to incorporate the ACARA Digital Technologies syllabus. The expectation was that a new document would be released that would incorporate the skills, understandings and knowledge described in the ACARA syllabus alongside the existing Science & Technology syllabus.

The result is something different. What we have is a document with a focus on the application of approaches to thinking, problem finding and solving empowered by science and technology. It is perhaps a curriculum that will get students and teachers excited about science and technology. It also brings new challenges.

Read the curriculum and you discover a combination of the familiar alongside new ideas and a new emphasis. According to the syllabus:

Science and Technology K–6 is an integrated discipline that fosters in students a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world around them and how it works. Science and Technology K–6 encourages students to embrace new concepts, the unexpected and to learn through trialing, testing and refining ideas. (NESA, 2017 p12)

This is not a Science syllabus with an emphasis on content knowledge but one that encourages students to engage with the practices of the scientist, the curious explorer who embraces unexpected learning and has the skills to construct new knowledge.

These skills enable students to participate responsibly in developing innovative ideas and solutions in response to questions and situations relevant to personal, social and environmental issues. (NESA, 2017 p12)

It should be noted that unlike all other current syllabus documents, this one is aimed at students between Kindergarten and Year Six (5 to 12 year olds. The skills and dispositions described here are not those to be developed by students as they exit school but are the expectations for learners in their primary years; learning goals to be achieved before they enter high school. There is evidence here that contemporary thinking about curriculum design has found its way into NESA (NSW Educational Standards Authority):

Students studying science and technology are encouraged to question and seek solutions to problems through collaboration, investigation, critical thinking and creative problem-solving. (NESA, 2017 p12)

Use of the word “through” is worth noting. It is reminiscent of models for the curriculum developed by Alan Reid who suggested that a set of essential competencies should be the priority for the curriculum and that other content should be taught “through” the application and development of these competencies. In the science and technology syllabus you find:

Through the application of Working Scientifically, and Design and Production skills, students develop an interest in and an enthusiasm for understanding nature, phenomena and the built environment. (NESA, 2017 p14)

The knowledge and understanding in Science and Technology K–6 are developed through the skills of Working Scientifically, and Design and Production. (NESA, 2017 p24)

In this syllabus science is something that students do, a tool for exploration and inquiry rather than a knowledge base.

Through regular involvement in applying these skills in a variety of situations, students develop an understanding that the Working Scientifically processes are more than a series of predictable steps that confirm what we know. (NESA, 2017 p26)

This is very much so a syllabus that is entered on active and agentic students. Phrases abound such as 'Students question and make predictions', 'They pose relevant questions', 'Students explore', Students make observations', 'They use appropriate materials'.

There is also much here that supports the maker movement, indeed it is a required element of learning that students will engage with an active process of product evaluation, design, modification and production.

They question and review existing products, processes and systems, explore needs or opportunities for designing, define problems to be solved, (NESA, 2017 p27)

Students develop and apply a variety of skills and techniques to create products, services or environments to meet specific purposes. They select and use materials, components, tools, equipment and processes to safely produce designed solutions. (NESA, 2017 p27)

And across both Design & Production and Working Scientifically students are required to engage in practical activities, to learn by doing and by making with tools and materials. 'Students must undertake a range of practical experiences to develop knowledge, understanding and skills in Science and Technology’ (NESA, 2017 p25)

There is also a significant emphasis on thinking and the syllabus identifies four modes of thinking which are at the heart of STEAM learning. Computational Thinking, Design Thinking and Systems Thinking join Scientific Thinking to ensure that 'Productive, purposeful and intentional thinking underpins effective learning in Science and Technology.’ (NESA, 2017 p35) As the syllabus notes this will require scaffolds for students and strategies that they can deploy as they engage with opportunities to apply their thinking skills 'as they encounter problems, unfamiliar information and new ideas.’ (NESA, 2017 p35)

The scope of the syllabus is exciting and potentially engaging. If taught well and as intended it should go a long way to preparing students for future learning challenges. As an integrated approach to STEAM based learning with science, technology and approaches to problem solving at its heart it offers students opportunities to use their skills and knowledge in concerted efforts to solve problems that matter. How such an integrated approach to this type of learning is to be maintained as students enter Stage Four and the siloed world of disciplines that is typical in High School is not made clear. Will student find that science learning beyond primary school is not what they expected it to be even if what they have become used to is more closely aligned to the real world of science and technology?

The challenge is to provide Primary School teachers with the support in all its forms for this syllabus to be fully realised. Professional development, modelling of practice, mentoring and resources will be required. Genuine inquiry, design and production of the type outlined in this syllabus is both messy and comes with ‘unexpected’ costs. All of this will need to be planned for and the costs of this factored into budgets. Now that the document is available for implementation schools will need support in bringing it to life.

By Nigel Coutts