Possibly the most dangerous place to spend too much time is inside your comfort zone. Only when we take a risk and step away from the safety of the familiar and the ways we have always done things do we expose ourselves to new ideas and become open to the possibility of learning and discovery. The trouble is having the confidence to take that first step, to embrace discomfort and become open to the risks that come with trying something new.

For our young students, school can be a place of constant leaping from one zone of discomfort to the next. Their learning journeys, particularly during the formative years are steep and there are many challenges. The social world of school brings one set of challenges. Time away from home and the safety net of their immediate family requires brave hearts and caring teachers who build bridges of support and care. Moving towards more formalised learning requires great curiosity but school brings the new experience of making mistakes in public. New teachers with each year of learning, different classrooms, shifting friendships and an always evolving curriculum brings a constant stream of challenges and opportunities to embrace the discomfort of the new.

Some of our young learners embrace these challenges with resilience and determination. Some become adept at avoiding challenges of a type they may not feel comfortable with. The realms in which we are willing to take risks gradually shrinks and our comfort zone expands. Before long we are developing a set of protective measures that allow us to spend more and more time inside our comfort zone. Slowly the list of things we don’t do expands. For learners, this pathway to a fixed mindset in certain areas of our learning can have a profound effect. Maybe it is in art where we decide it is not a subject for which we have the required skills. Perhaps it is mathematics that we turn away from. Maybe we believe that there are people who can do maths and people who can’t, and we are in the ‘I can’t’ group.

As teachers, our responsibility is to guide our students away from their comfort zones and back into Vygotsky’s ‘Zone of Proximal Development’. We show them that the risk is not as great as they imagine and provide the safety net they need. By understanding the obstacles they face, we can provide just the right support so they can move in the desired direction. Building their confidence, showing them it is OK to fail, that the little steps they are taking are moving them towards their goal even if they don’t see it. By providing the safe environment they need, full of feedback that guides and shows the way we can help our students move towards a growth mindset.

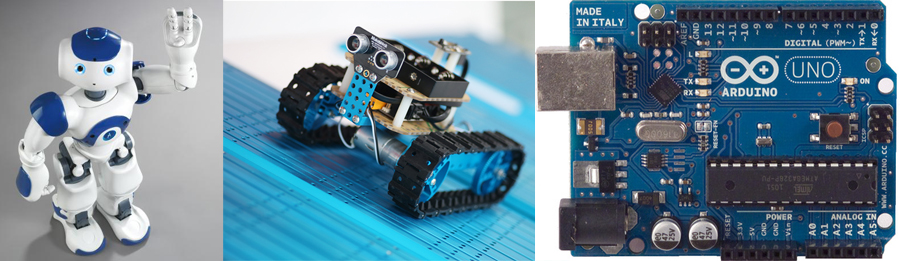

For some of our students the challenges they might face at school fall short of the edges of their comfort zone. These are the students who throughout their schooling achieve at an acceptable standard. They pass the tests, achieve success and nothing seems too difficult for them. For these students, school fails to provide a suitable challenge. These are the students whose first experience of cognitive dissonance, overwhelming complexity and the need to step outside their comfort zones arrives after their school years. Alone and without a caring guide at their side, these are the students who seemingly fail to cope with the world of work despite their great promise they once showed. The challenge is to identify these students and provide the opportunities they need to experience challenging learning while at school. It is interesting to note that for some students it is learning that occurs away from the traditional academic class that brings them face-to-face with real challenge. Maybe it is a learning experience in the great outdoors, where the elements, the isolation and the dramatic change of context shows gaps in their ability to cope. Some students who manage the day to day routine of the classroom find that the challenges typical of maker-centered learning are too much. Their understanding of geometry and physics seems to slip from their grasp as they struggle with the details of a mitered joint or the lines of code required to turn on a light bulb.

Teachers also have comfort zones. It is often said that the most dangerous phrase in education is “That’s how we have always done that”. We are comfortable with the ways we teach. We are safe in our routines, safe when we are in control, safe when we know what to expect. We have our imagining of how school should look, what good teaching looks like and believe we know how to achieve this. Inside our classrooms we are masters of our domain. But what if we are wrong? How do we know our approach is best, how are we testing our understanding, how are we exposing ourselves to new ideas and maybe better ways of meeting our learners needs?

We need to step outside our comfort zones for the sake of our learners. Maybe this starts with opening our classroom doors and inviting others to observe our practice. Perhaps it starts with trying a new routine, a new approach to questioning, a new take on how we close a lesson. maybe we give up some of our control and hand the learning back to the students. What would it sound like if we were the quietest voice in the room, if we asked but one question and let the students run with it? Alan November asks the question “Who owns the learning?”, to encourage teaching that encourages curiosity and develops self-directed learners. What might our classrooms be like if no one in the room new the answer to the questions that are asked in advance?

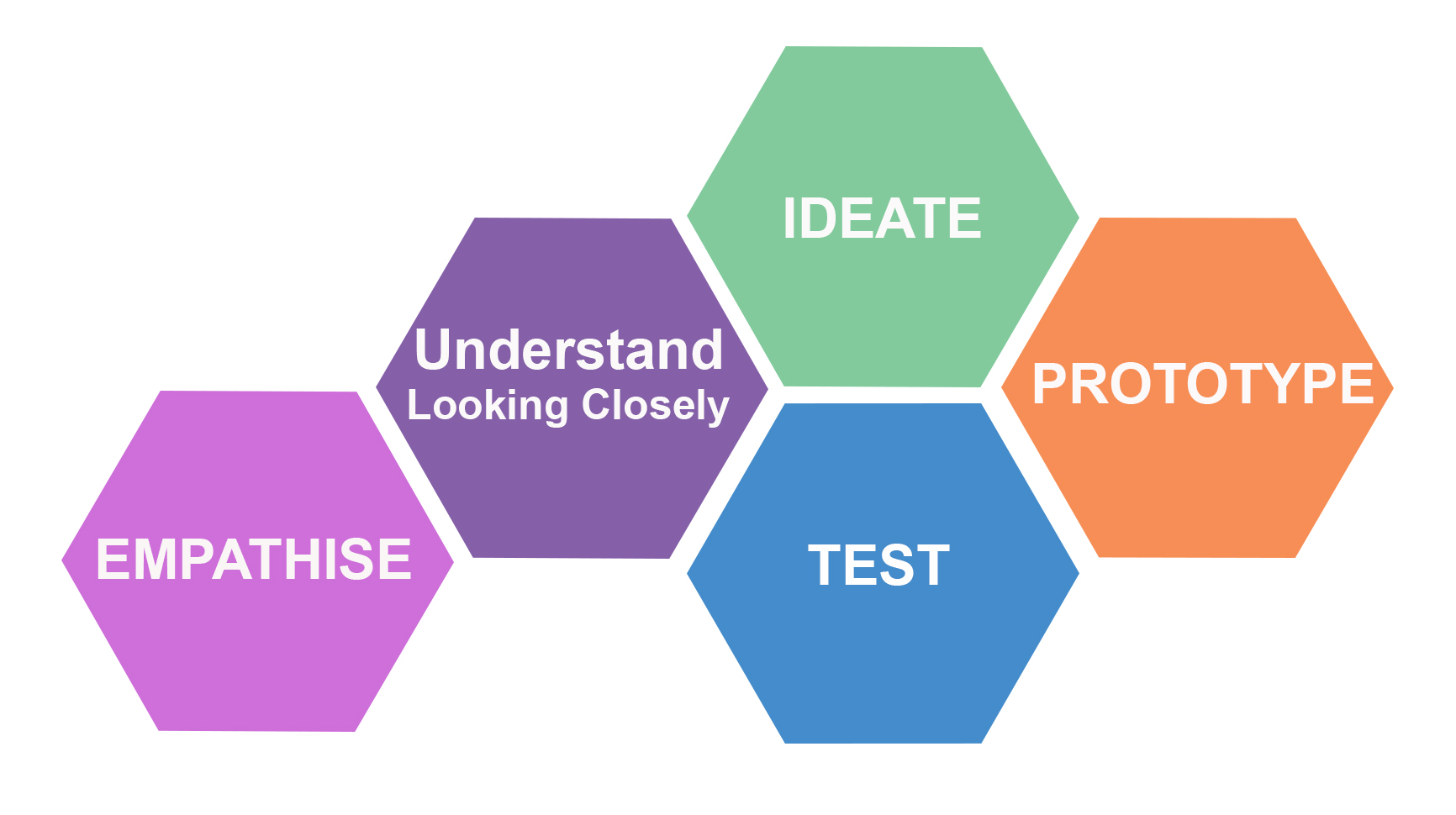

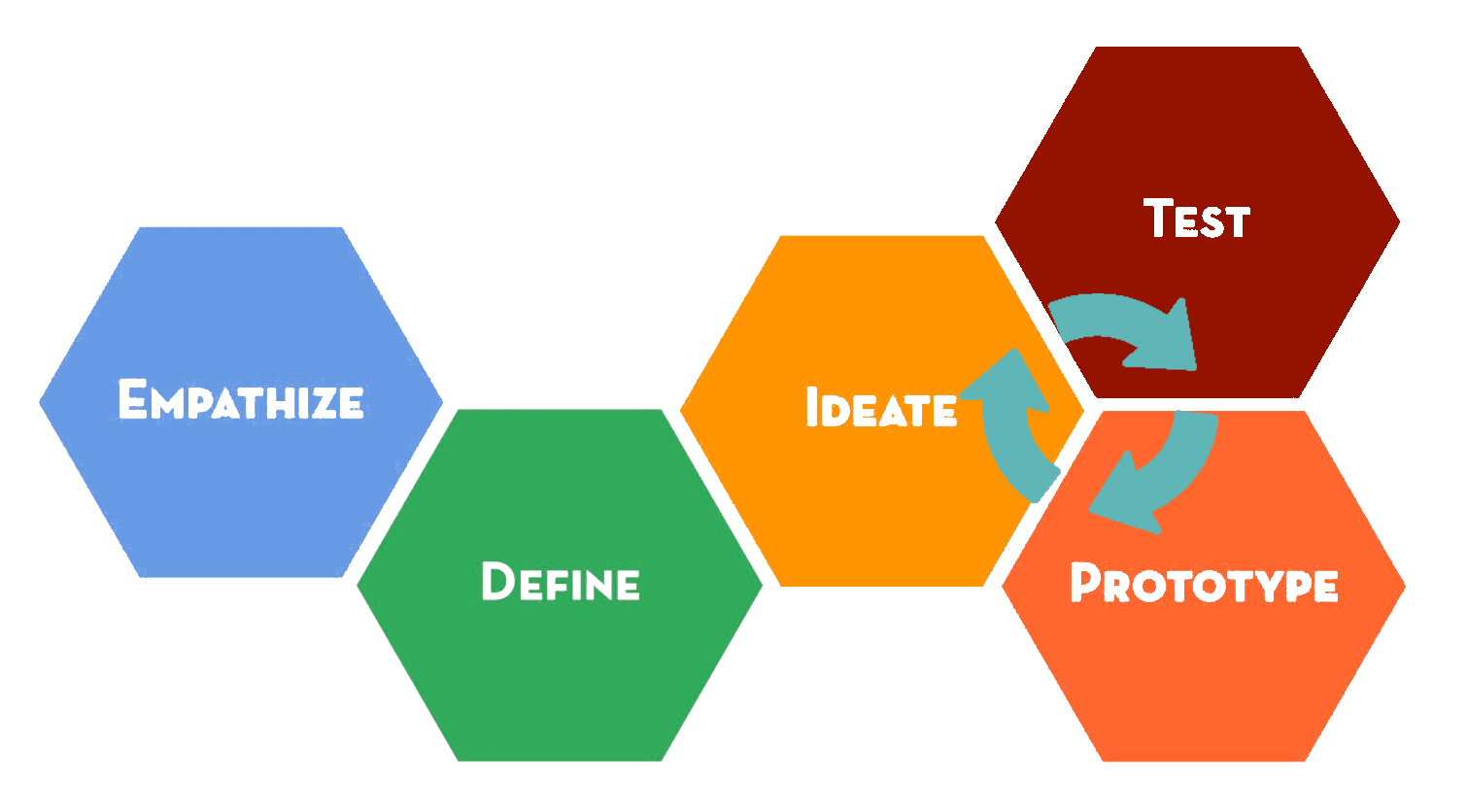

As we move from a model of education that sees the teacher as the sage on the stage to a guide on the side, all involved are likely to experience an expanded zone of discomfort. Our students will be required to do much more thinking, collaboration, problem finding and solving. Teachers will not always know how their lessons will evolve, where the learning might lead and there is likely to be more noise. Our classrooms should be a buzz with the energy of inquisitive minds. Questions will be asked for which there are yet no answers. David Perkins describes this elegantly "The agenda of education should not just be passing along the contents of already open boxes but fostering curiosity for those still unopened or barely cracked open.” By stepping outside of our comfort zones, by taking our students out of theirs, we begin a learning journey that will prepare them for a world of unknowns where their willingness to embrace the challenges they face is their strongest weapon.

By Nigel Coutts