Ask any teacher what they wish they had more of and the most common answer is likely to be time. Schools are inherently busy places and there is always much to be done. We all want to meet the needs of every student, add value to their education with breadth and depth, ensure adequate coverage of the curriculum and include aspects of play and discovery. Add up all that is done in a day over and above face-to-face teaching and you can only wonder at how we manage to fit it all into the time we have. So is there an answer to this dilemma, is there a secret method to finding more time in our schedules to achieve all that we want to?

It is not surprising that time is one of the eight cultural forces that Ron Ritchhart (2015) identifies as contributing towards a culture of thinking. In his book ‘The Eight Cultural Forces’ he describes the importance that time plays in signaling what we value. As time is such a valuable resource its allocation to particular aspects of teaching and learning signifies their value. If we give time to content and memorisation of facts, we signal to our students that this is what we value. Likewise, if we remind our students that time is short and work must be completed quickly we should not be surprised when our students see tasks as work to be done rather than learning to be mastered. A more effective distribution of our time will see students being given time to think deeply and truly engage with the problems they are asked to solve.

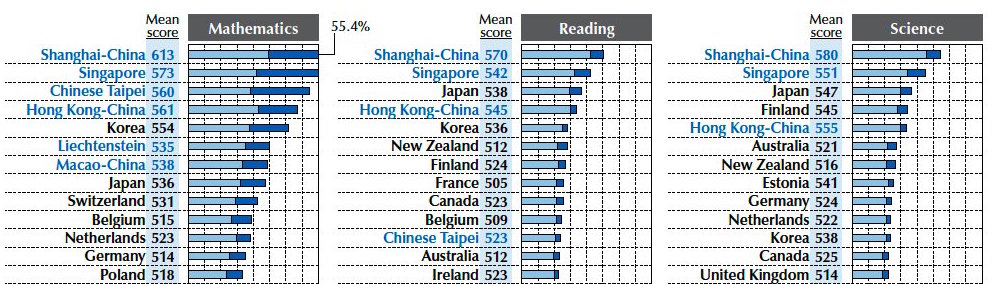

While much is made of the triad of signaling systems in schools (pedagogy, curriculum & assessment) time and its distribution is often ignored in this role. For our students how we locate time sends important messages about what constitutes important learning. Unsurprisingly maths and English top the billing for time distribution in schools. Down the list come other subject areas and towards the bottom are those which can be pushed aside as schedules fill up. The bottom of this list may also include the development of so called soft skills, those which are difficult to assess and are not directly seen in assessment results. The importance of these soft-skills including important aspects of socio-emotional learning, creativity and even critical thinking are often not given the time they deserve.

For students the time they are given to think and reflect on their learning is critical to the quality of their learning. Ritchhart (2015) quotes research that reveals the power of wait time and thinking time with the quality and quantity of student thinking increasing by 300% to 700% when additional time is given to thinking within class discussion. Wait time or thinking time combined with strategies such as those from ‘Making Thinking Visible’ signify to students that what is wanted is not a speedy response but a well considered one. Wait time and thinking time according to Ritchhart combat the habit many students develop of guessing what the teacher wants as a response. While most frequently considered an approach to improving the quality of class discussion the use of effective and appropriate wait time is also shown to increase the quality and quantity of students' written responses which reinforces the notion that teaching and encouraging our students to think will improve their exam results along with the overall quality of their thinking with resultant benefits for their quality of life.

For teachers, time in the day is always short and there are many things to be done before the lights are turned off and the door closed at the end of the day. Often, the workday follows us home in the form of marking and emails disturbing family and personal time. Within our busy days we find that there are elements which drain our energy reserves and others which leave us enthused and looking for the next challenge. Mindfulness and reflective practices that allow us to identify which parts of our day give us positive energy compared to those that do not is a step towards achieving balance. Self-determination Theory (SDT) as described by Ryan & Deci (2000) and as discussed in Daniel Pink’s (2009) work on motivation reveals three drives that help us engage and maintain enthusiasm. Autonomy or a sense of control is a part of this triad and although we may not be able to decide which tasks we complete or not we can probably determine the order they are approached. Scheduling tasks which give us a boost of energy early in the day might help us move through the challenging middle period while finishing with a task we enjoy can be a positive ending. Putting off the tasks we enjoy least, those which offer the leas rewards until the end of the day is a recipe for disaster.

The other two drives identified by SDT are purpose and mastery. These too are linked to time and shape our perception of a task as a positive or negative experience. The perceived purpose of a task, the degree to which a task is important to us, the intrinsic enjoyment that a task has play an important part in how we value the time we spend on it. If a task is closely connected to our core purposes it is likely to be valued and time spent on is hardly noticed. The opposite is true and it is tasks that seem to block us from achieving important goals which will be most grudgingly assigned time. Stepping back from such negative tasks and looking for their connection to our grander goals may shift our perception. Within SDT the desire to master a task is the third drive. Mastery in most instances takes time and situations which prevent us from achieving mastery can lead to negative feelings. Being realistic with our mastery goals and recognising that true mastery is only achieved after significant time may reduce feeling of anxiety when confronted by situations where mastery is the goal but success is difficult to achieve.

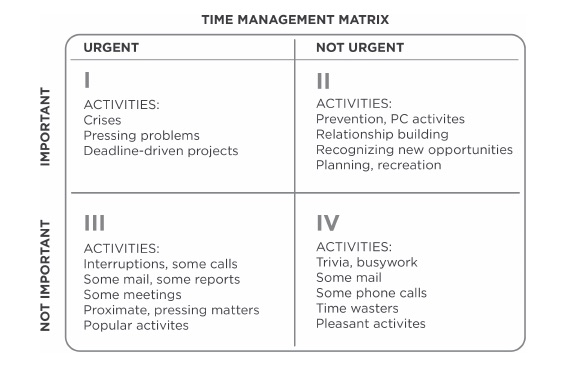

Time management and the identification of which tasks are most engaging and uplifting is addressed effectively by the work of Stephen Covey. His time management matrix shows a correlation between a task's perceived importance and its urgency with tasks deemed important but not-urgent being the ones which allow us to produce our best work. This concept is similar to the idea of wait time or thinking time and the ideas are linked together in Ritchhart’s writing. Unfortunately in schools tasks which should be in the quadrant of not-urgent but important end up due to scheduling and poor time distribution in the important/urgent box that results in reactive and low quality thinking. Collaborative planning, reflection, problem identification and solution are areas that demand our best thinking but are not always given the time they demand. What this reveals is that the problem many schools face is not one of quantity of time but rather allocation of time. By identifying the aspects of a school’s life that most require our best time and with that our best thinking we may achieve more effective results but also avoid creating many of the negative situations which then rob us of even more time.

Our best work occurs in quadrant two, Important/Not Urgent.

Perhaps what is most needed in schools is the inclusion of time as an agent item. By talking about how we use time, where we need more time, how we may better distribute our use of time to signal importance and provide opportunities for students and teachers to achieve their best with the time they have we begin to move things forward. Being open to new solutions, breaking with tradition and valuing time as we value money are steps towards a better model for time management in schools, one that has benefits for all.

Covey, S. (2015) The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Interactive Edition. Mango Media inc.

Pink, D. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Ritchhart, R. (2015) Creating cultures of thinking: The eight forces we must truly master to transform our schools. SanFrancisco: Josey-Bass

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78