There is a general consensus amongst teachers that the curriculum is overly full. I am yet to meet a teacher who espouses a belief that they have sufficient time to cover all of the material that they are supposed to teach. Part of the challenge here is the ever-expanding breadth of the curriculum as a whole. It seems that as society confronts each new challenge, schools are expected to add a new area of study. Keep an eye for Pandemic Preparedness as an addition to the K-6 Curriculum alongside Coping with Isolation and How to Plan for a Bushfire. It seems that someone in a policy office imagines that school timetables are printed on sheets of rubber and can expand to accommodate each new learning objective. In addition to the breadth of subjects and special interest topics that must be covered, is the great depth of curriculum content that is required in each key learning area. Finding time to cover all of this while engaging the students in meaningful learning, rich thinking and experiences that build understandings are considered the greatest challenges confronting most educators.

In most instances the claim that the curriculum is overcrowded is valid and indeed this has been backed by multiple studies including an extensive report prepared by the Australian Primary Principals Association (PDF). In response to this, Federal and State Governments have both promised curriculum reviews with the hope of delivering a streamlined curriculum. Internationally the situation is the same as reflected by Singapore’s policy of “Teach Less, Learn More” and the broad interest that this approach has gained. Whether this curriculum streamlining will target the right content to be culled is certainly open for debate. One response is the typical back to basics approach, which translates into a renewed emphasis on drilling core literacy and numeracy skills. Another approach requires a re-thinking of what learning matters most to students in the lives that they are likely to live. This approach invites a close exploration of the purposes of education and invites an analysis of what's worth learning.

The tendency to make a leap from the claim that the curriculum is overcrowded to a solution based upon streamlining the curriculum is very natural. One begins to explore questions such as “Why is the curriculum overcrowded?” and “How did it become so overcrowded?” and these are certainly questions that might need to be asked. There is also a tendency to skip another possibility, one that relies on an understanding that there are always multiple curriculums in play.

Allow me to explain further. There is the curriculum that is intended, the one written by curriculum writers, endorsed by government agencies and published to schools. This intended curriculum is then interpreted by teachers and the result is what might be referred to as the implemented curriculum. It is the implemented curriculum that sits most closely to the experienced curriculum. The interpreted curriculum is what results from the planning process and it is these programmes that teachers subsequently teach from. At this layer, the teacher is blending their understanding of the curriculum with their knowledges of the discipline, of pedagogy and their students. This interpreted curriculum is then delivered to students by teachers who may or not have been involved in the planning process and this leads us to what might be referred to as the experienced curriculum. As implied, the experienced curriculum is that which is delivered to students in the classroom and the interpretation of this curriculum must include the perspective of individual students. Many factors will shape the impact of the experienced curriculum and any interpretation of this curriculum that does not account for individual differences and societal diversity will be flawed.

When we speak of an overcrowded curriculum we must be clear on which curriculum we are referencing. In many cases, we will be speaking of the intended curriculum and the hope will be that the next version of the curriculum will better meet our needs. This results in a collective finger-pointing and lengthy waiting as we hope for a curriculum that is focused on what matters most according to those who share our beliefs and a fear that those whose beliefs are contrary to this might have more of a say. This mindset results in a belief that the curriculum is beyond a teacher’s realm of influence.

The belief that curriculum overcrowding can only be solved by a shift in policy or an act of government ignores the important part that teachers play in interpreting the curriculum. By shifting our perspective to the interpreted curriculum some level of agency is returned to the teacher. We also begin to see that some of the curriculum overcrowding results from how the curriculum is interpreted and it is worth considering how this process occurs.

I would like to propose that one cause of curriculum overcrowding is a phenomenon I refer to as “Idea Creep”. Just as a creeper vine grows and takes over more and more space, so too do ideas expand and grow in complexity. This can be seen frequently when one closely compares the requirements for a concept or outcome as defined by the intended curriculum of a jurisdiction with what is implemented. Often one finds that the intention of the curriculum writer has been expanded upon and that content intended for the learners at the next level is introduced early. This tends to be common in mathematics and the sciences and particularly in Primary learning environments.

It seems that teachers will consider the concept that they are asked to teach and in place of considering how to incrementally build an understanding of this concept dive into teaching all that they know about it. As an example, in the New South Wales curriculum students are gradually introduced to the concept of three-dimensional shape. The curriculum clarifies multiple steps from novice learner to competent mathematician. In Stage One (Years One and Two) students are expected to be able to describe, represent and recognise familiar three-dimensional objects, including cones, cubes, cylinders, spheres and prisms. They need to know the difference between a two-dimensional shape and a three-dimensional shape, use some formal vocabulary, describe which attributes of shapes they used when sorting them, make models of shapes in a variety of means and explain how the models were made. Students at this level do not need to know what makes a cube special, they do not need to know why a triangular-prism is named thusly, they do not need to be able to identify a shape from its net and they don’t need to understand isometric projection.

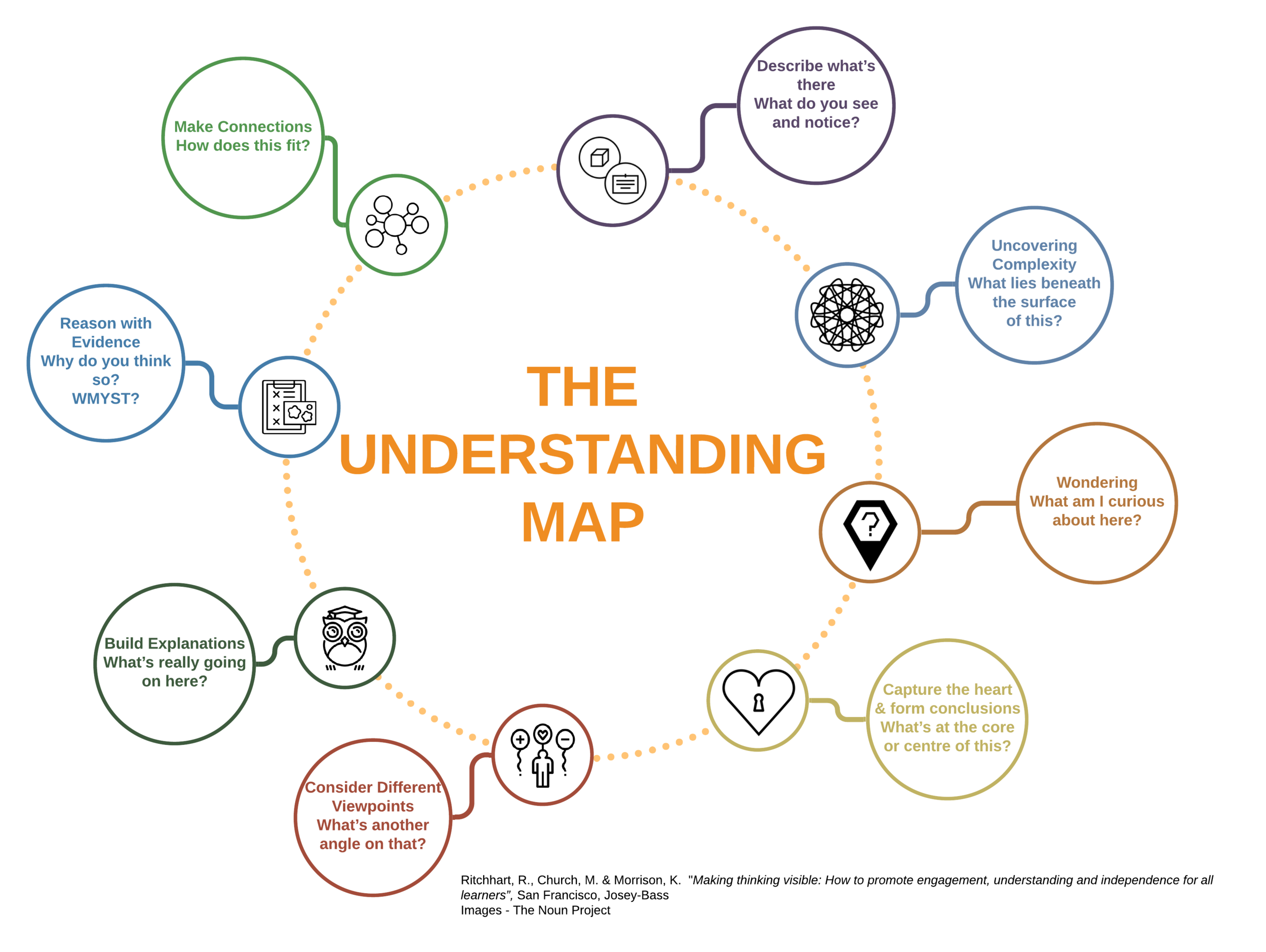

A visual interpretation of the NSW Stage One 3D Shape content.

At least some part of the challenge of a bloated curriculum might be resolved if we are able to understand what results in “Idea Creep” and how this might be reduced. Certainly part of the blame for this lies with the manner in which curriculum documents are written. Lengthy introductions, wordy rationales, multiple pages of outcomes and content and all of this written in language that is at best unfriendly to the average time-poor teacher. If a teacher is lucky they may have an hour or two release time to prepare a given teaching programme and are most likely looking after more than one key learning area if they are not singularly responsible for them all. Who can blame a teacher in these circumstances for reading the headline and jumping straight into what they plan to teach? Who in this situation has the time to decipher the code and sort the wheat from the chaff? Part of the challenge also is likely to stem from the need for primary teachers to have expertise across multiple domains, many of which they do not have expertise or significant training in.

What then might be the solution? Firstly teachers need curriculum documents that are written to be read and interpreted on the fly. Highly visual curriculum documents which clearly identify what needs to be taught and when might ensure “Idea Creep” is minimised. Further, teachers need more time to interpret the curriculum and access to more support in doing so. Spectacular learning experiences are planned for and delivered when teachers are given the time to engage in meaningful collaborative discussion about the curriculum. If the goal is to produce students who have a deep-understanding of the curriculum we also need teachers who have a deep-understanding of it. This understanding is not developed simply from years of experience but from the opportunity to spend time immersed in the curriculum.

Hopefully an awareness of the dangers of “Idea Creep” will result in a fresh approach to, and broader perspectives on, some of the challenges of curriculum overloading.

By Nigel Coutts