Contemplating the effects of traditional mathematics in "A Mathematicians Lament", Paul Lockhart wrote

"If I had to design a mechanism for the express purpose of destroying a child’s natural curiosity and love of pattern-making, I couldn’t possibly do as good a job as is currently being done - I simply wouldn’t have the imagination to come up with the kind of senseless, soul-crushing ideas that constitute contemporary mathematics education.”

The traditional pedagogy of Mathematics encourages students to see the discipline as one that requires them to memorise and recall on demand a set of procedures and isolated facts. Speed and correct answers are overemphasised at the expense of understanding and genuine number fluency. As students focus on learning the procedures they fail to make a connection with the logic behind the methods they are using. They develop fundamental misconceptions and develop a narrow and shallow mathematical knowledge.

Retention of information through rote practice isn't learning; it is training. (Ritchhart, Church & Morrison. 2011)

This traditional pedagogy results in students developing a negative attitude towards mathematics. Many develop a mathematical phobia and believe that they are not a "maths person". When confronted by challenging mathematics they retreat and have no or only poor strategies with which to approach new ideas. This all leads to a decline in the number of students pursuing mathematical learning beyond the years where it is compulsory.

Fortunately there is a growing body of research that shows there is a better way.

This approach to mathematics is structured around a set of core ideas and practices. Each element works with each other element to build Mathematical Confidence for the learner. Mathematical Confidence is achieved when the learner believes that they are able to reason, communicate and problem solve with mathematical concepts. Mathematical confidence requires a deep level of understanding, adaptive expertise, fluency and a growth mindset when confronted with mathematical challenges.

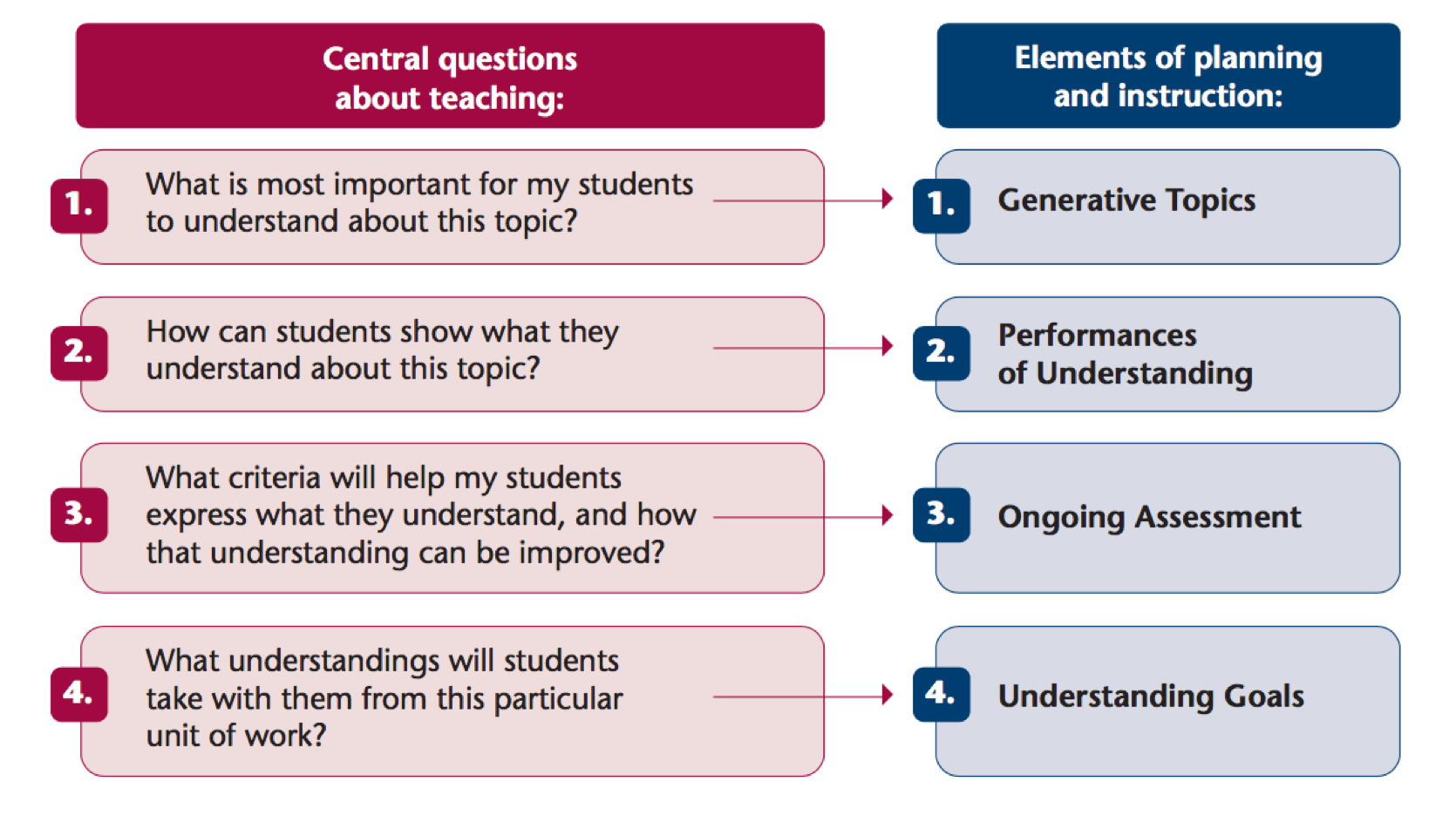

Through Number Talks students develop a rich Number Sense, a capacity to manipulate, de-compose and re-compose numbers, notice patterns and communicate mathematical ideas. By visualising, playing with and investigating "Big Ideas" students develop their understanding of essential concepts in mathematics. Strategies from "Visible Thinking" provide structures for student thinking and make this thinking observable to their teachers. Engagement in real-world, open-ended problems provide students with opportunities to apply their mathematical skills and reveals the relevance of mathematics beyond the classroom. By employing a "Teaching For Understanding" framework to their planning and pedagogy, teachers ensure the focus of mathematics is on developing adaptive expertise and ensures students experience opportunities to demonstrate and refine their understanding. The result is Mathematical Confidence defined by ones ability to bend their mathematical knowledge to new situations, to incorporate new concepts into their existing scheme and embrace challenges with a growth mindset.

Where to begin? Understanding the impact of our instructional order

Typically, the lesson begins with the teacher presenting the required method to the students. The teacher begins with step one being demonstrated on the board. Once step one is complete, the teacher demonstrates step two, and then step three and sometimes steps four and five. With triumphant zeal the teacher indicates the correct answer with a flourish of whiteboard marker and perhaps a double underline for effect. In phase two the students copy the process they have been shown with the teacher looking on to ensure the steps have been followed accurately. Naturally there are some bugs and errors that require correction. By the end of the lesson most students are able to accurately follow the steps and arrive at a desirable answer even if some of the numbers are changed.

Compare this to how a computer is programmed. The ‘coder' determines the steps to be completed and enters them into the machine ensuring accuracy; this equates closely to phase one of our lesson although with our students the coding occurs visually and aurally rather than via keyboard. The coder then runs the code on the computer and looks for bugs in the code which may cause unwelcome results; this is phase two of our lesson. Finally, having checked the code and feeling confident that it is bug free and fit for purpose the coder releases their programme into the world where it runs on a range of subtly different systems and with a mix of inputs; a very near comparison to phase three of our lesson.

The focus is on mimicry and memorization rather than deep mathematical thinking and understanding, flexible use of mathematical concepts, communication of mathematical arguments and justifications, and developing a positive disposition that values connections between mathematics and students’ identities beyond the classroom. I think it is important that mathematics teachers use instructional routines that not only build procedural fluency through conceptual understanding but also support strategic competence, adaptive reasoning, and productive dispositions. (NCTM President - Robert Berry)

There is a better way, one that supports conceptual understanding.

The alternative approach is to present content in a sequence that allows students to develop their number sense while also engaging in exploration of concepts or Big Ideas (through visualisation, play & investigation), with opportunities to problem-solve and problem-find as ways of strengthening their capacity for working mathematically. At the point of need in this cycle, new content including mathematical methods can be taught through targeted instruction with the goal to always build understanding.

This approach to organising the presentation of content is built on three research based beliefs:

1. Mathematical understanding requires students to engage first with concepts rather than procedures.

2. Engagement and learning is increased when students see a need for the methods they are being taught

3. Instructional sequences which begin with problem solving allow for learning through 'productive failure'

1. Unless mathematics is to be viewed as a discipline defined by rules, where success is determined by how accurately one follows those rules, learning must begin with the underlying concepts (Big Ideas). This is backed by research from Australia's Chief Scientist that examined the approach taken to mathematics in 619 Australian schools achieving significantly above expected growth. "87% of case study schools had a classroom focus on mastery (i.e. developing conceptual understanding) rather than just procedural fluency."

2. We are more likely to engage with new ideas when we see how they will help us achieve a short term goal. Telling students you will need this in the future, or worse, you will need this for the test is unlikely to increase motivation. When what we are learning has immediate relevance, when we are clear on the purpose of what we are learning our intrinsic motivation is triggered according to Daniel Pink, author of Drive. (Learn more about 'Drive' in this Video)

Jo Boaler et al., shares the following research that reveals the power of teaching mathematical processes at the point of need, rather than in isolation of need and in advance of application to contexts that matter to the learner.

A really interesting research study (Schwartz & Bransford, 1998) showed that students learned more when they worked, using their intuition, on problems that needed methods, before they learned the methods. They did not learn the methods until they had encountered a need for them. This caused the students' brains to be primed to learn them.

Boaler, Munson, Williams. (2018) Mindset Mathematics: Visualizing and Investigating Big Ideas, Grade 5 (p. 249). Wiley.

This approach of teaching to big ideas and teaching smaller ideas when they arise, has the advantage of students always wanting to learn the smaller methods as they have a need for them to help solve problems. (Boaler, Munson, Williams. What is Mathematical Beauty? Teaching through Big Ideas and Connections YouCubed )

3. Manu Kapur describes an instructional order "that reverses the (traditional) sequence, that is, engages students in problem solving first and then teaches them the concept and procedures. (He) call(s) this sequence of problem solving followed by instruction productive failure". Kapur's research shows that "Productive failure students, in spite of reporting greater mental effort than Direct Instruction (DI) students,significantly outperformed DI students on conceptual understanding and transfer without compromising procedural knowledge". (Kapur)

The aim is to ensure students develop the number sense, capacity for working mathematically and mathematical confidence they need along with an understanding that mathematics is a visual and beautiful subject.

By Nigel Coutts

This post has been adapted from ‘Global Cognition’ a site that is being developed by the author of this blog to support teachers implement this approach in conjunction with their use of the ‘Mindset Mathematics’ series by Boaler, Munson & Williams and the NESA Mathematics Curriculum.